Hace unos días, cuando volví a consultar el libro The Elements of Photography, Understanding and Creating Sophisticated Images (Elementos de la fotografía, comprensión y creación de imágenes sofisticadas) por Angela Faris Belt, encontré una cita del fotógrafo Misha Gordin en el prólogo:

«El concepto pobre perfectamente ejecutado todavía hace una mala fotografía.»

A few days ago, when I revisited the book The Elements of Photography, Understanding and Creating Sophisticated Images by Angela Faris Belt I came across this quotation by the photographer Misha Gordin in the preface:

“The poor concept perfectly executed still makes a poor photograph.”

Angela Faris Belt hace referencia a la discrepancia que existe entre las prácticas comerciales y las obras de arte en la fotografía. Por un lado, muchos fotógrafos de arte crean imágenes que se basan en conceptos maravillosos, pero dado que muchos de ellos no son plenamente conscientes de gran parte de la técnica de la fotografía, sus creaciones se quedan cortas. Me gusta la forma en que Belt compara estos artistas con «poetas que poseen habilidades gramaticales limitadas». Por otro lado, muchos fotógrafos comerciales tendrán un amplio conocimiento técnico, pero siguen siendo fotógrafos «sin educación en las áreas de la historia de la fotografía y del arte, la alfabetización visual, la teoría crítica y la estética». Lo cierto es que encontrar el equilibrio entre estos dos lados puede ser lento y difícil, ya que exige la aplicación continua y diligencia de profundizar en los temas que son más abstractos y, a menudo alejados de la vida cotidiana.

Angela Faris Belt gives an account of the discrepancy that exists between commercial and fine art practices in photography. On the one hand, many fine art photographers create images that are based on wonderful concepts, but since many of them are not fully aware of much of the technical side of photography, their creations fall short. I like the way Belt likens these artists to “poets possessing limited grammatical skills”. On the other hand, many commercial photographers will have ample technical knowledge, but remain “undereducated in the areas of photography and art history, visual literacy, critical theory, and aesthetics”. Indeed, finding the balance between these two sides can be time consuming and difficult, since it demands continuous application and diligence in delving into topics that are more abstract and often remote from everyday life.

Con respecto a lo anterior, creo que la parte artística es mucho más compleja, básicamente, porque ¡no se puede escribir poesía con sólo aprender la gramática! Se requiere mucho más: la inteligencia, la sensibilidad, la profundidad, y un sentido de la naturaleza efímera del mundo. Esto no quiere decir que el aprendizaje de detalles técnicos demostrados en la fotografía comercial sea menos exigente, sino más bien, que los dos dominios hacen demandas distintas en el practicante.

Looking at these two sides, I find the fine art part much more complex, essentially, because you cannot write poetry just by learning grammar! It requires a so much more: intelligence, sensitivity, depth, and a sense of the ephemeral nature of the world. This is not to say that mastery of technicalities demonstrated in commercial photography is any less demanding, rather that the two domains make such different demands on the practitioner.

Y hablando de la fotografía artística, no te puedes perder la exposición actual Broken Promise de Leónidas Espinelli en Mistos. Me parece interesante que en los descansos entre clases muchos de nosotros estemos inconscientemente atraídos por las imágenes, tratando de entender el significado de las fotografías austeras y provocativas. Honestamente puedo decir que nunca he pasado tanto tiempo mirando las fotografías en Mistos antes; algo me obliga a contemplarlas e inspeccionarlas repetidas veces. La capacidad de las imágenes para mantenerse frescas y sugerentes, habla de la fortaleza de la serie.

And speaking about fine art photography, you must not miss the current exhibition “Broken Promise” by Leónidas Espinelli at MISTOS. I find it interesting that in the breaks between lessons many of us are unconsciously drawn to the pictures, trying to derive meaning from the stark and – not to say the least – provocative photographs. I can honestly say I have never spent so much time looking at the photographs in MISTOS before; something compels me to contemplate them, to inspect them repeatedly. The ability of the pictures to stay fresh and evocative, speaks to the strength of the series.

Decidí examinar el trabajo de tres fotógrafos de arte conceptual muy distintos, para enfatizar que la búsqueda de un concepto fuerte no tiene una receta; más bien implica que tienes que encontrar tu propio camino y seguirlo de manera consistente ya sea instintiva o analítica. Sin embargo, todos estos artistas comparten un rasgo importante: son sistemáticos y sus fotografías son buenas porque son buenos conceptos «perfectamente ejecutados».

I decided to look at the work of three very different conceptual art photographers, to emphasize that finding a strong concept does not have a recipe; it rather implies that you have to find your own way and following it consistently whether that is instinctive or analytical. However, all these artists share one important trait: they are systematic and their photographs are good because they are good concepts “perfectly executed”.

Misha Gordin

El fotógrafo estadounidense nacido en Letonia Misha Gordin comenzó a tomar fotos a la edad de 19 años, pero estaba decepcionado con los resultados, que transmitían simplemente lo que él veía en vez de lo que él sentía. Buscando una manera de expresar su visión personal con un estilo distinto, decidió fotografiar conceptos, creando su primero en la imagen que en 1972 llamó Confession (Confesión).

The Latvian born, American photographer Misha Gordin started taking photos at the age of 19, but was disappointed with the outcomes, which conveyed merely what he saw as opposed to what he felt. Seeking a way of expressing a personal vision and style, he decided to photograph concepts, creating his first such image in 1972 called Confession.

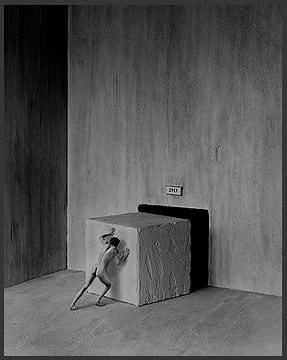

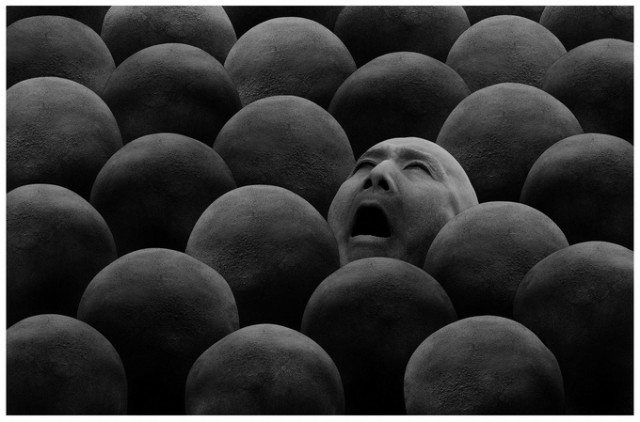

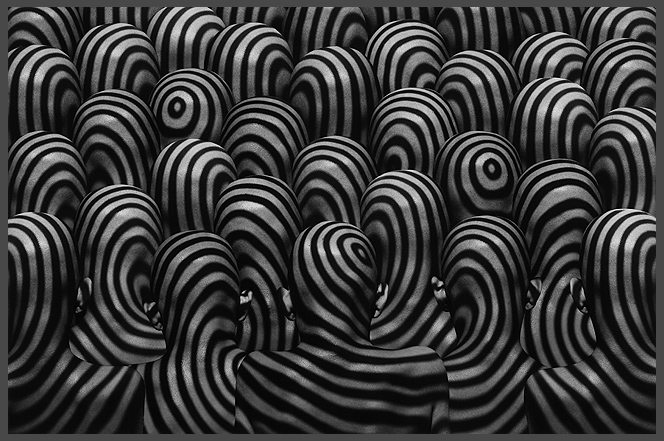

La realización exitosa de su visión en Confession abrió un mundo de posibilidades ilimitadas para el artista de revelar la esencia de la vida en forma cada vez más abstraída, y con claras alusiones a la alienación y a los sentidos de represión y opresión. Sus imágenes funcionan en muchos niveles: pueden ser apreciadas por la habilidad formidable necesaria para ejecutarlas con la fotografía analógica, así como por su carácter simbólico. Debajo de las capas de elementos repetitivos y simétricos, siempre hay mensajes para comprenderlas conscientemente o de manera intuitiva.

The successful realisation of his vision in Confession opened up a world of limitless possibilities for the artist to disclose the essence of life in ever more abstracted form, and with clear allusions to alienation and senses of repression and oppression. His images work on many levels: they can be appreciated for the formidable craft required to execute them by analogue photography as well as for their symbolic nature. Underneath the layers of repetitive and symmetric elements, there are always messages to be consciously distilled or intuited.

Puedes ver la imagen con cabezas de la gente (de la serie New Crowd) como un mundo de la conformidad que encarcela aún a los que no se amoldan, o puedes optar por renunciar a ti mismo a la sensación de alienación que surge de la imagen. También puedes contemplar el absurdo de las situaciones presentadas, parecidas al mundo en las obras de Samuel Beckett.

You might choose to regard the image of heads of people (from the series New Crowd) as a world of conformity that imprisons even those who do not conform, or you might opt for resigning yourself to the feeling of alienation that emanates from the picture. You could also contemplate the absurdity of the situations depicted, not unlike those brought to life in Samuel Beckett’s plays.

Según Gordin: «¿Qué verdad se puede encontrar en la imagen manipulada?,¿qué sería digno de confianza sobre visiones de un mundo que no existe externamente? ¿Y qué más da? A mí me importa. La traducción de los conceptos personales en el lenguaje de la fotografía refleja posibles respuestas a las grandes preguntas del ser: el nacimiento, la muerte y la vida. La transformación de un concepto en realidad es una parte esencial de la fotografía conceptual, e impregna a esta con la realidad que resuena con la esfera interior de la experiencia de la gente, como en la pintura, en la poesía, en la música y en la escultura. La fotografía conceptual emplea el talento especial de la visión intuitiva”.

Gordin says: “What truth can you find in the manipulated image, what is trustworthy about visions of a world that does not externally exist? And does it matter? To me it matters. The translation of personal concepts into the language of photography reflects possible answers to the major questions of being: birth, death, and life. The transformation of a concept into reality is an essential part of conceptual photography, and imbues it with the reality that resonates with one’s inner sphere of experience, as in painting, poetry, music, and sculpture. Conceptual photography employs the special talent of intuitive vision.”

«No interpreto mis imágenes. Los siento. Sin embargo, siempre animo a mis espectadores a interpretar mi trabajo como lo que ven o sienten. Mi objetivo es crear una imagen que habla. «Misha Gordin

“I don’t interpret my images. I feel them. Nevertheless, I always encourage my viewers to interpret my work as they see or feel it. My goal is to create an image that talks.” Misha Gordin

Cindy Sherman

La fotógrafa y directora de cine estadounidense Cynthia (Cindy) Morris Sherman es famosa por sus retratos conceptuales en los que hace preguntas sobre la forma en que las mujeres son percibidas y representadas por los medios de comunicación y en la sociedad en su conjunto. Cuando trabaja en estos retratos, Sherman prefiere la soledad de su estudio, donde ella misma asume todos los papeles – modelo, fotógrafa, artista de maquillaje, peluquera, etc. – necesarios para la creación artística de distintos personajes. Los escenarios espartanos de sus imágenes son compensados por los trajes elaborados y el maquillaje que lleva.

The American photographer and film director Cynthia (Cindy) Morris Sherman is famous for her conceptual portraits in which she questions the way women are perceived and represented by the media and in society as a whole. When working on these portraits, she prefers solitude in her studio, where she assumes all the roles – model, photographer, make-up artist, hairstylist, etc. – necessary to bring different characters to life. The spartan settings of her images are offset by the elaborate costumes and make-up she wears.

«Todo el mundo piensa que son autorretratos pero no están destinados a ser. Sólo uso a mí misma como modelo porque sé que puedo esforzarme en los extremos, hacer cada disparo tan feo o bobo o tonto como sea posible.» Cindy Sherman

“Everyone thinks these are self-portraits but they aren’t meant to be. I just use myself as a model because I know I can push myself to extremes, make each shot as ugly or goofy or silly as possible.” Cindy Sherman

Sherman describe su proceso creativo como intuitivo: «Pienso en convertirme en una persona diferente. Me miro a mi mismo en un espejo junto a la cámara… es como estar en trance. Mirándome fijamente en el espejo trato de ser ese personaje a través de la lente… Cuando veo lo que quiero, mi intuición se hace cargo – tanto en el ‘actuar’ como en la edición. Ver esa otra persona que está allí arriba es lo que quiero. Es como magia…»

Sherman describes her creative process as intuitive: «I think of becoming a different person. I look into a mirror next to the camera… it’s trance-like. By staring into it I try to become that character through the lens… When I see what I want, my intuition takes over – both in the ‘acting’ and in the editing. Seeing that other person that’s up there, that’s what I want. It’s like magic.”

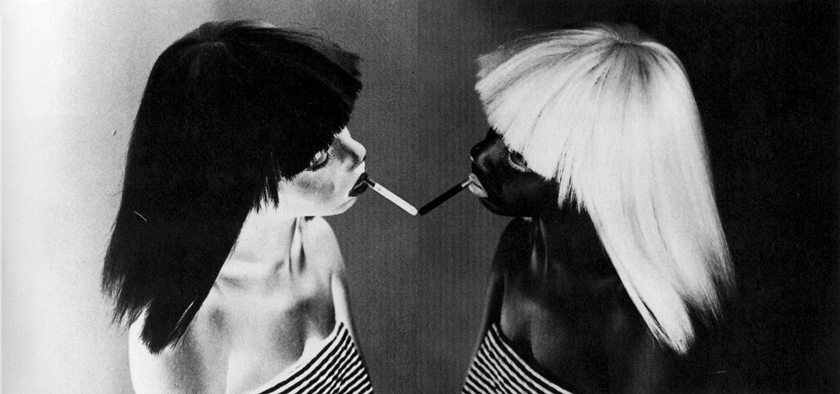

Sherman saltó a la fama con su serie Untitled Film Stills, 1977-1980, que incorpora 69 fotografías en blanco y negro que se asemejan a fotogramas individuales del film noir americano y de las películas de neorrealismo italiano. MoMa compró la serie en 1995.

Sherman rose to fame with her Untitled Film Stills series, 1977-1980, which incorporate 69 monochrome photographs that resemble individual frames from film in the American film noir and Italian neorealism traditions. MoMa purchased the series in 1995.

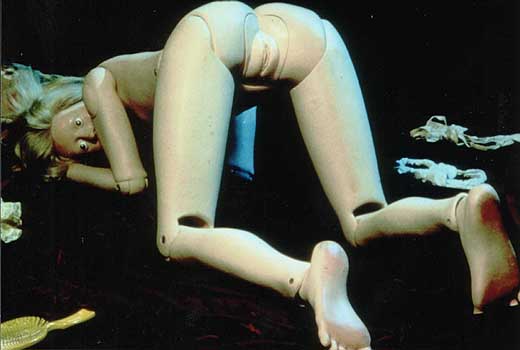

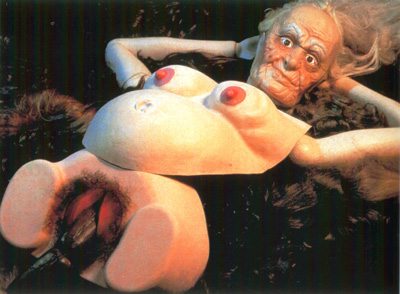

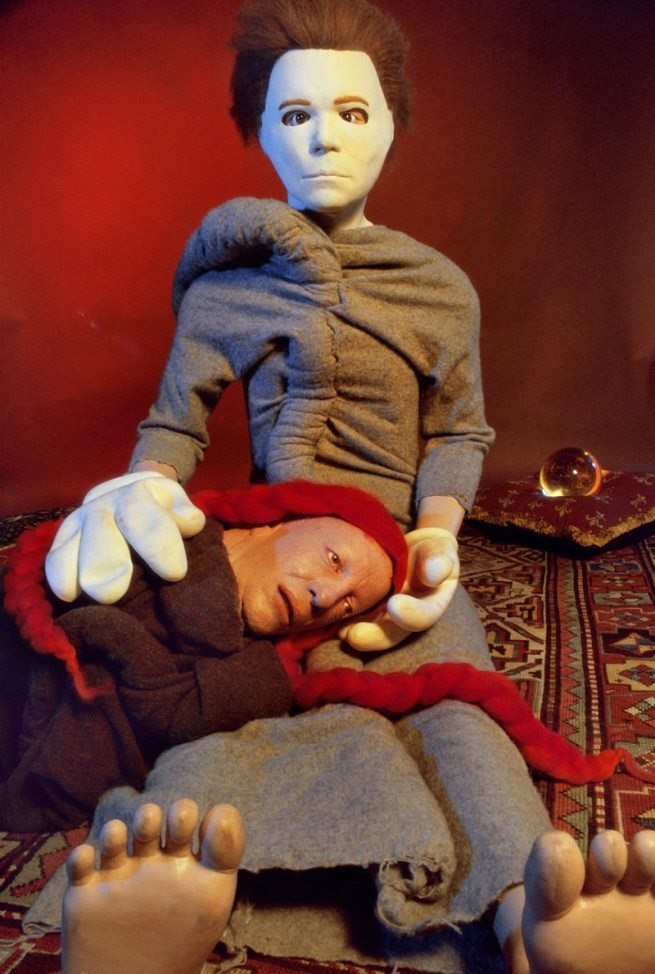

La serie Sex Pictures, contra lo que se espera, no contiene imágenes pornográficas como se entiende en el sentido tradicional; en cambio, Sherman obsequia al espectador con maniquíes y extremidades protésicas que aluden a cuestiones importantes en torno a la cosificación de las personas y la relación entre el sexo y la violencia.

The Sex Pictures series, contrary to expectation, does not contain pornographic images as understood in the traditional sense; instead, Sherman presents the viewer with mannequins and prosthetic limbs that allude to important issues surrounding the objectification of people and the relationship between sex and violence.

«No analizo lo que estoy haciendo. He leído interpretaciones convincentes de mi trabajo, y a veces me he dado cuenta de algo de que no era consciente, pero creo que, en este momento, la gente interpreta mi trabajo por costumbre. O soy muy, muy inteligente. «Cindy Sherman

“I don’t analyse what I’m doing. I’ve read convincing interpretations of my work, and sometimes I’ve noticed something that I wasn’t aware of, but I think, at this point, people read into my work out of habit. Or I’m just very, very smart.” Cindy Sherman

“We’re all products of what we want to project to the world. Even people who don’t spend any time, or think they don’t, on preparing themselves for the world out there – I think that ultimately they have for their whole lives groomed themselves to be a certain way, to present a face to the world.” Cyndi Sherman

«Cuando veo una fotografía de un personaje trato de copiarla a mi cara. Creo que soy muy observadora, y pensando en la composición de una persona, verla en la calle y me fijo en las cosas sutiles sobre porque esas son las cosas que los hacen lo que son. «Cindy Sherman

“I’ll see a photograph of a character and try to copy them on to my face. I think I’m really observant, and thinking how a person is put together, seeing them on the street and noticing subtle things about them that make them who they are.” Cyndi Sherman

John Hilliard

El artista conceptual británico, John Hilliard, inicialmente utilizó la fotografía para inmortalizar sus propias instalaciones temporales, pero muy pronto se interesó por los mitos que rodean a la veracidad de la imagen fotográfica y así se embarcó en una investigación de los prejuicios inherentes en la fotografía, destacando la selectividad del fotógrafo en la composición y la exposición de una imagen con el resultado de que el significado de la imagen resultante también es muy flexible y sujeto a la manipulación.

The British conceptual artist, John Hilliard, initially used photography to immortalize his own temporary installations, but very quickly became interested in the myths surrounding the truthfulness of the photographic image and so embarked on an investigation of the biases inherent in photography by highlighting the selectivity of the photographer in composing and exposing a picture with the result that the meaning of the resulting image is also highly flexible and subject to manipulation.

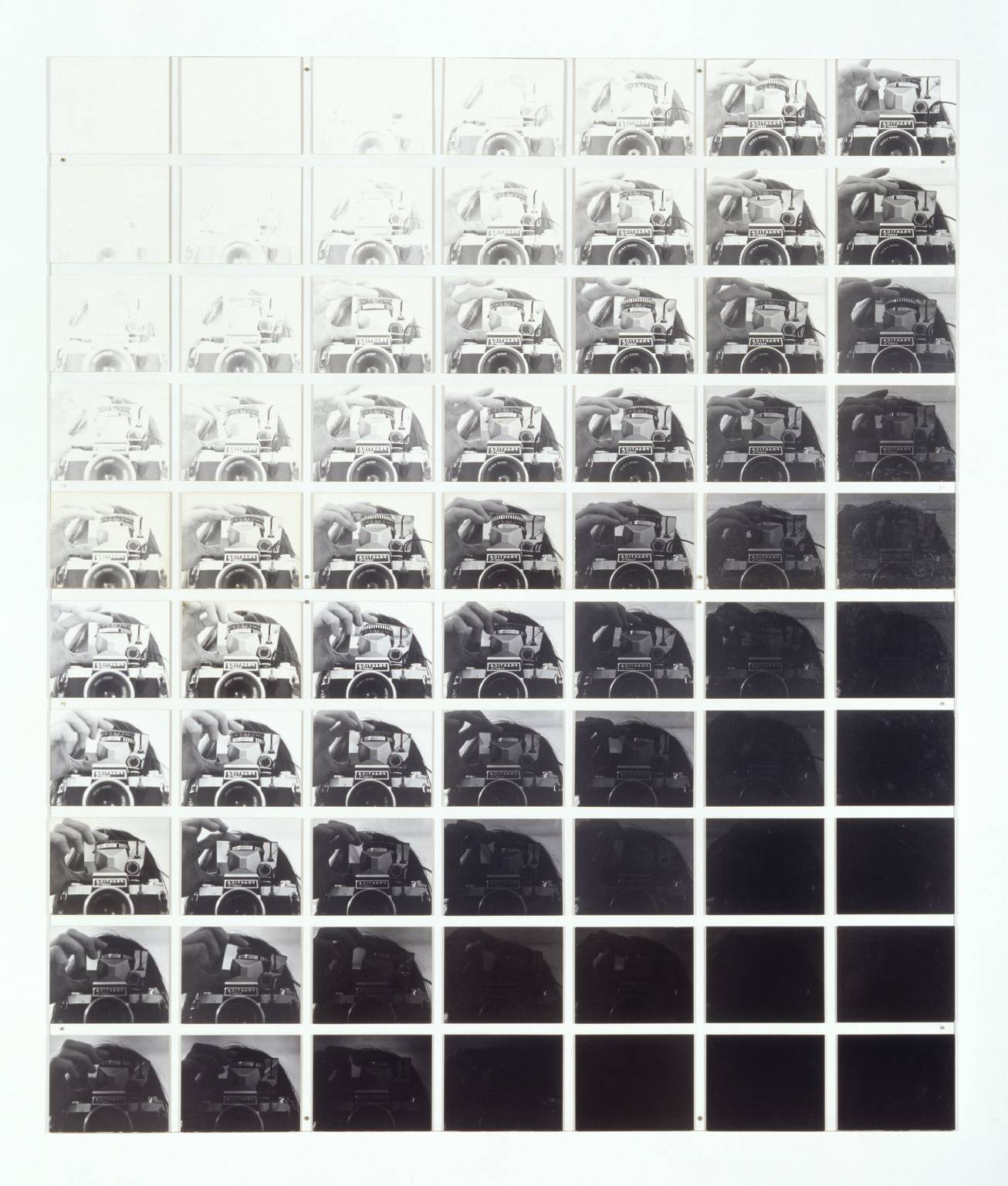

Desde la década de 1970 Hilliard decidió dedicarse totalmente a la fotografía. Su trabajo Camera Recording Its Own Condition, 1971, se compone de setenta imágenes monocromos de la reflexión de una cámara y la mano del artista en el momento de tomar una foto. El artista cambió la apertura y la velocidad de la cámara, así grabando toda la escala de exposiciones desde una imagen totalmente subexpuesta hasta la imagen sobreexpuesta, aludiendo así a la intervención humana que dicta la imagen resultante procedente de una cámara supuestamente objetiva.

From the 1970s on Hilliard decided to dedicate himself fully to photography. His work Camera Recording Its Own Condition, 1971, consists of seventy monochrome images of the reflection of a camera and the artist’s hand at the moment of taking a picture. The artist changed the aperture and speed of the camera, recording the full range of exposure from an over-exposed image down to totally under-exposed, thereby alluding to the human intervention that dictates the resulting image coming from a supposedly objective camera.

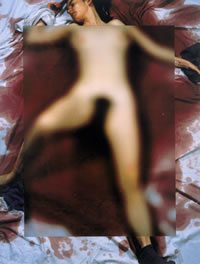

Causes of Death, 1974 trae a nuestra atención el proceso de edición que puede afectar la manera en que concebimos una imagen. El artista crea una serie de cuatro imágenes del mismo objeto – un cuerpo muerto – cubierto con una sábana blanca, pero recortando ligeramente diferente que crea un nuevo contexto de significado, por lo que el espectador asocia inmediatamente la muerte con un cierto tipo de accidente. Es un maravillosamente simple ejemplo de que somos propensos a la proyección de nuestro propio pensamiento sobre las imágenes, creando así nuestras propias historias.

Causes of Death, 1974 brings to our attention the editing process that can affect the way we conceive an image. He creates a series of four images of the same subject – a dead body – covered in a white sheet, but by cropping them slightly differently he creates a context of meaning, so the viewer immediately associates the death with a certain kind of accident. It is a wonderfully simple example of us being prone to projecting our own thought onto the images thereby creating our own stories.

Con la imagen del East/West, 1986 Hilliard examina cuestiones de identidad y asimilación cultural. Mediante el uso de lo negativo y positivo de la misma fotografía, llama la atención sobre lo insignificante que muchas de las diferencias físicas son, la misma mujer aparece como blanco y negro, pero por debajo de la superficie, hay valores que nos unen a todos.

With the image East/West, 1986 Hilliard examines issues of identity and cultural assimilation. By using the negative and positive of the same photograph, he draws attention to how insignificant many of the physical differences are, the same woman is featured as black and white, but underneath the surface, there are values that unite us all.

Desde la década de 1980 en adelante, Hilliard incorporó la fotografía en color a su repertorio, de tal manera que examinó y criticó a los medios de comunicación que saturan nuestras vidas con fotografías. Por la década de 1990 empezó a producir imágenes de colores vivos y saturados » con narrativas eróticas y, a veces violentas, y [imágenes] con efectos de superficie brillante que emulan o al menos hacen referencia a la seducción de la publicidad.» (Sara Jayne Parson: Enciclopedia de la fotografía del siglo XX)

From the 1980s onwards, Hilliard incorporated colour photography into his repertoire, examining and criticising the mass media that saturates our lives with photographs. By the 1990s he started producing colourful and saturated “images with erotic and sometimes violent narratives, and glossy surface effects which emulate or at least reference the seductive power of advertising.” (Sara Jayne Parson: Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Photography)

Hilliard comienza su proceso de creación con una serie de dibujos y escrituras, que le llevan a la composición fotográfica apropiada, por lo que detrás de la imagen resultante hay un análisis intelectual riguroso y de contemplación.

Hilliard starts his process of creation with a series of sketches and writings, which lead him to the right photographic composition, so behind the resulting image there is a rigorous intellectual analysis and contemplation.

Me gustaría terminar con una cita de mi historiador de arte favorito, Sir Ernst Gombrich (británico, pero nacido en Austria) cuya descripción de ilusión encaja bien con lo que pienso sobre el misterio del arte:

I would like to finish with a quote from my favourite art historian, Sir Ernst Gombrich (British but Austrian born) whose description of illusion fits in wonderfully with what I think about the mystery of art:

«Cualquier persona que puede manejar una aguja convincente puede hacernos ver un hilo que no está allí. El truco de la magia se convierte en arte cuando un mago como Charlie Chaplin realiza una danza con un par de tenedores y un par de panecillos que se convierten en piernas ágiles en frente de nuestros ojos.» (Arte y Ilusión)

“Anyone who can handle a needle convincingly can make us see a thread which is not there. The conjuring trick is turned into art when a magician such as Charlie Chaplin performs a dance with a pair of forks and a couple of rolls that turn into nimble legs in front of our eyes.” (Art and Illusion)

El arte de la fotografía es inseparable de la idea y su ejecución.

The art of the photograph is inseparable from both the idea and its execution.